User Networks

An Alternative to Primary Intended Users

A major adjustment that many evaluators have to make is from academic research to professional consulting practice. The audience of academic research is conceived of as a community of one's peers. Biochemists conduct research designed to be read and used by all the other biochemists. Sometimes academics create a simplified version of their work for the media, and in this case the audience is even larger. Professional research consultants have much smaller, more specific audiences. We are hired by clients who would like us to write reports for their organization or a tiny subset of it. Recently I wrote a 30-page needs assessment for a three-person architectural firm. When I transitioned from doing academic work to consulting this was one of the biggest adjustments I had to make. My audience appeared to have shrunk from "anyone with expertise in this area" to "Jane, Mike, and Terry at the Department of Public Health."

It was while I was making this transition that Michael Quinn Patton's framework of utilization-focused evaluation (UFE) started to make sense to me. Patton argues that, in order to orient evaluations towards use, we need to identify the primary intended users (PIUs) of the evaluation results and tailor the evaluation project to their needs. This idea helped me complete my pivot into professional research consulting - here was a defensible theoretical reason for shaping evaluations around the client's needs rather than my own standards. I no longer felt strange about moving technical details into endnotes or creating executive summaries that left them out entirely. My reports and presentations became pithier as I stopped chasing down every little lead that came up and started to focus on adding more detail about what the client really needed to know.

However, as I matured in my evaluation practice, I began to notice something odd about the search for primary intended users. I found myself working on several evaluations in which the primary intended users were either impossible to identify or unwilling to be engaged. For example, some of my evaluations were funded by local-level agencies who needed to report their activities to state-level agencies. The state-level agencies were certainly the PIUs - they were actively using the evaluations to set policy and make funding decisions - but they were not interested in coming to meetings with me or shaping the evaluations in any way beyond the occasional audit (in which they never had any feedback on the evaluations).

I had an opportunity recently to ask Michael Quinn Patton: how would I conduct a utilization-focused evaluation in this case? Patton very graciously responded to my question: we have to make a sincere effort to identify and engage PIUs, but if we cannot, the evaluator needs to step up and act as the PIU. I found this response reassuring in a practical sense because it described what I had in fact done several times. In a theoretical sense, however, I was left with a nagging concern. When I take over the role of determining the main parameters of the evaluation that the PIU would normally determine, such as the evaluation questions, this doesn't actually make me the evaluation user. The evaluation user is still out there somewhere, waiting to use the evaluation - but, like God, they just aren't interested in talking to me right now. Doesn't this fact make the evaluation non-utilization-focused? I didn't think of this question fast enough to ask it during our conversation, but I can imagine a couple of reasonable responses: 1) true UFE was already made impossible when the PIUs were not able to be engaged, so this is no longer a UFE anyway, or 2) it is still a UFE because the "use" of the evaluation has shifted to merely "completing an evaluation." Neither of these answers appears satisfactory, since the first one simply gives up the point that evaluator-managed evaluations can be UFEs and the second one makes the evaluation into useless paperwork. I don't wish to put words in Patton's mouth, but maybe one day I'll get a chance to continue the conversation.

A more theoretical concern I have about PIUs is about ontology. Namely, what kinds of things are primary intended users? Patton has been clear over the years that organizations cannot be PIUs - only individual people can. In an interview four years ago Patton was quite direct about this:

"[Prior to utilization-focused evaluation] the entire evaluation field was based upon the notion that organizations use information - the institutions. So people do evaluations for Congress. And my response is Congress doesn't exist. There's no such thing. Congress can't do shit. Congress is an artifact. People. So who are the committee heads? Who are the staff who are going to take stuff to their congressperson? Who are the board members? Who are the directors? That you have to connect with people and the facade of 'I'm providing information to a board or an institution or to something else' keeps them from dealing with 'who are the people who are going to use the information and how do I connect with them.'"

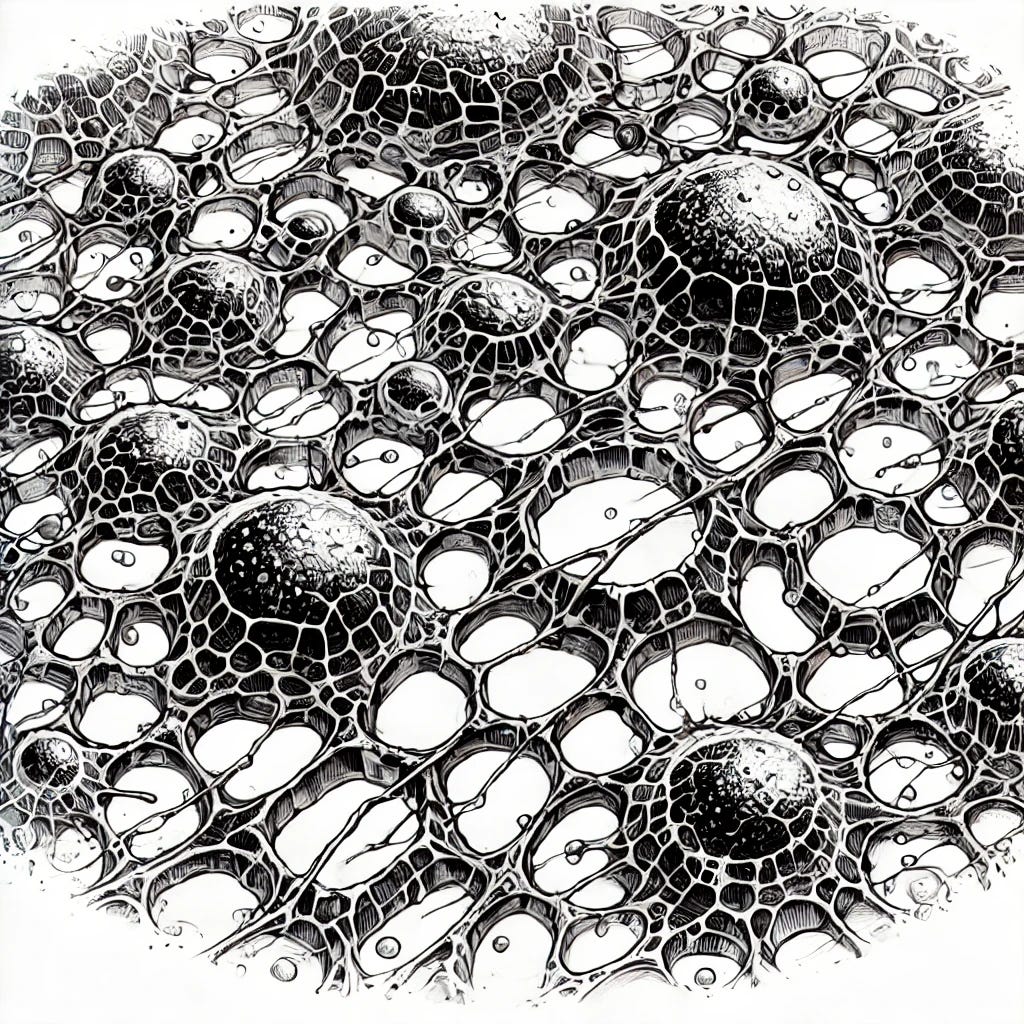

This is just as much a statement about ontology as it is about approach. Organizations don't exist. There are only individual people. If we had to coin a label for this ontology, we might call it "nominalistic eliminativism" - a belief that only particular, concrete entities exist, such as individual humans, objects, or physical processes, that rejects the reality of abstract constructs like organizations, states, or other emergent structures. In this ontology, such constructs are mere linguistic conveniences with no independent ontological status. There are versions of nominalism (the belief that certain abstract entities are "mere names") that are very helpful at times, but a common issue with nominalism is that it has trouble dealing with emergence. Emergence is what happens when entities at a lower level of organization gain in function by working together, thus creating higher level entities that play by different rules. Emergence is the reason that it would deliberately obtuse to say that "you" are "just" a gaggle of cells that have chosen to cooperate. By denying the existence of higher-level entities, nominalists end up denying obvious emergent structures that have their own priorities.

Organizations are an excellent example of emergent entities. The thread of organizational theory known as natural systems theory carries this insight to its logical conclusion by likening organizations to organisms: organizations behave as though they have their own drives and instincts for survival and growth that go far beyond what individual humans intend: balancing budgets, cutting inefficiencies, switching goals, expelling troublemakers. In the branch of sociology known as actor-network theory, we would say that organizations are networks which can themselves be actors. Organizations are non-human assemblages - even if they are partly composed of humans - but this doesn't mean that they can't be actors. This is why it actually makes sense to say that "Congress" or "OpenAI" or "China" has done something - these entities are capable of organizing themselves to accomplish emergent functions that the individuals comprising them cannot accomplish.

So what can this ontology tell us about primary intended users? Actor-network theorists would say that the users of evaluations are almost always networks rather than individual people. Individuals can't usually do much with evaluations - networks can. If we are writing a report for the ranking member on the Housing committee, we are writing to her specifically because of her role in the network. In the case I mentioned above, the network of evaluation users was fairly dense at the local level, with a distant connection to the state level, where the decisions were actually made. I needed to write a report that would satisfy my local client while also keeping in mind how this absent stakeholder would be reading my report. In a word, I was writing for a network, and the way I wrote needed to remain cognizant of the precise shape of that network.