What are criteria and where do they come from?

Rebecca M. Teasdale on the domains and sources of criteria (2021)

Choosing and applying criteria is essential to evaluation. When we say that something is "good" or "bad", we are implicitly invoking some criteria for our appraisal. In formal evaluations, we make criteria explicit so that others can judge whether they are the correct ones to use under the circumstances. The classic model of evaluation, codified by Michael Scriven (1980), involves four steps:

select criteria

set performance standards based on criteria

gather data on the performance of the evaluand

synthesize results into a final value judgment

We’ll have a lot to say about this model of evaluation in future articles, but for now, let’s focus on just the first step: selecting criteria. What are criteria and where do they come from?

In this post, I introduce a way of thinking about the content and sources of criteria, from Rebecca M. Teasdale's 2021 article "Evaluative Criteria: An Integrated Model of Domains and Sources." In her paper, Teasdale assembled a corpus of guidance about criteria in program evaluation and created a list of the different kinds and sources of criteria. This list is very helpful for when you are trying to decide what exactly to evaluate about a program. I find that thinking about criteria before I formulate evaluation questions is much easier than thinking about them afterwards. If the evaluation questions can't be cashed out in terms of criteria, they probably aren't really evaluation questions but some other kind of question.

Before I explain Rebecca Teasdale's helpful model of criteria, however, I want to lay out a few simple truths about criteria. These truths help us understand what kind of things criteria are and are not.

Characteristics of criteria

There are many possible criteria

In an evaluation, we may differ on which criteria we are invoking. I think that the Toyota Prius is a good car - my criteria include reliability, gas mileage, and safety. A sports car enthusiast whose criteria are top speed and aesthetics would likely conclude that the Prius is not a good car. This is not a threat to the idea of criteria as long as we can agree that, if we were to use the same criteria, we would conclude that the same cars are good. There are many possible criteria for an given evaluand, but there usually aren't infinite possible criteria - a group of people tasked with listing all the potential criteria for an evaluand will usually top out after a couple of dozen, most of which are admittedly not very important.

There are many ways to rank criteria in importance

In my car example, I might be able to come to an agreement with the sports car enthusiast about the overall list of criteria to use to evaluate cars. For example, we could say that reliability, gas mileage, safety, top speed, and aesthetics are all acceptable criteria. However, it is often perfectly reasonable to differ on which criteria are the most important. I want a car that will get me to work but my friend wants a car that is fun to drive. There is nothing wrong with this in principle, since my friend and I belong to different user networks distinguished by different purposes. In principle, we could create a ranking of criteria that would be accepted by particular user networks.

Criteria interact

In everyday life, we find that criteria interact with each other in ways that produce or undermine our appraisals. The easiest example of this is price and quality. We are often prepared to accept mid-quality goods at low prices but would reject those same goods at high prices. An $80,000 Prius is not a good value, but an $80,000 Aston Martin is a steal. A car with low gas mileage might be considered good if it has a large passenger capacity, like a minivan, but not if it has a small passenger capacity. A car with a poor safety record, like the Ford Fiesta, might be unacceptable no matter what its other positive characteristics. Michael Scriven pointed out that the interactions between criteria are the reasons that we can't simply rate-and-sum all the criteria to get a "composite" score.

Criteria are not values

Values are beliefs about what is good that "transcend specific situations" (Teasdale, 2021). Criteria are specific observable characteristics against which the evaluand will be judged. Values help us to understand what criteria are important, but values are much more general than criteria. We can infer someone's values by looking at the criteria they select for appraising things, but this inference never certain. In my evaluation practice, I often find that stakeholders choose criteria that are easy to operationalize instead of criteria that really manifest their values. Improving our ability to construct measures is key to helping align values and criteria.

There are criteria for criteria

Evaluation necessarily involves judgements about whether the criteria we have selected are good. To make these judgments, we need to invoke criteria about criteria. These metacriteria include things like clarity, feasibility, and utility. For example, it is pretty easy to measure gas mileage but it is harder to measure aesthetic appeal, so a consumer magazine might not bother including the latter. Utilization-focused evaluation arguably boils down to a view about selecting metacriteria. While the idea of metacriteria might seem like we are entering into an infinite regress, there isn't really much further to go once we hit this second level - try it yourself if you like.

Domains and Source of Criteria

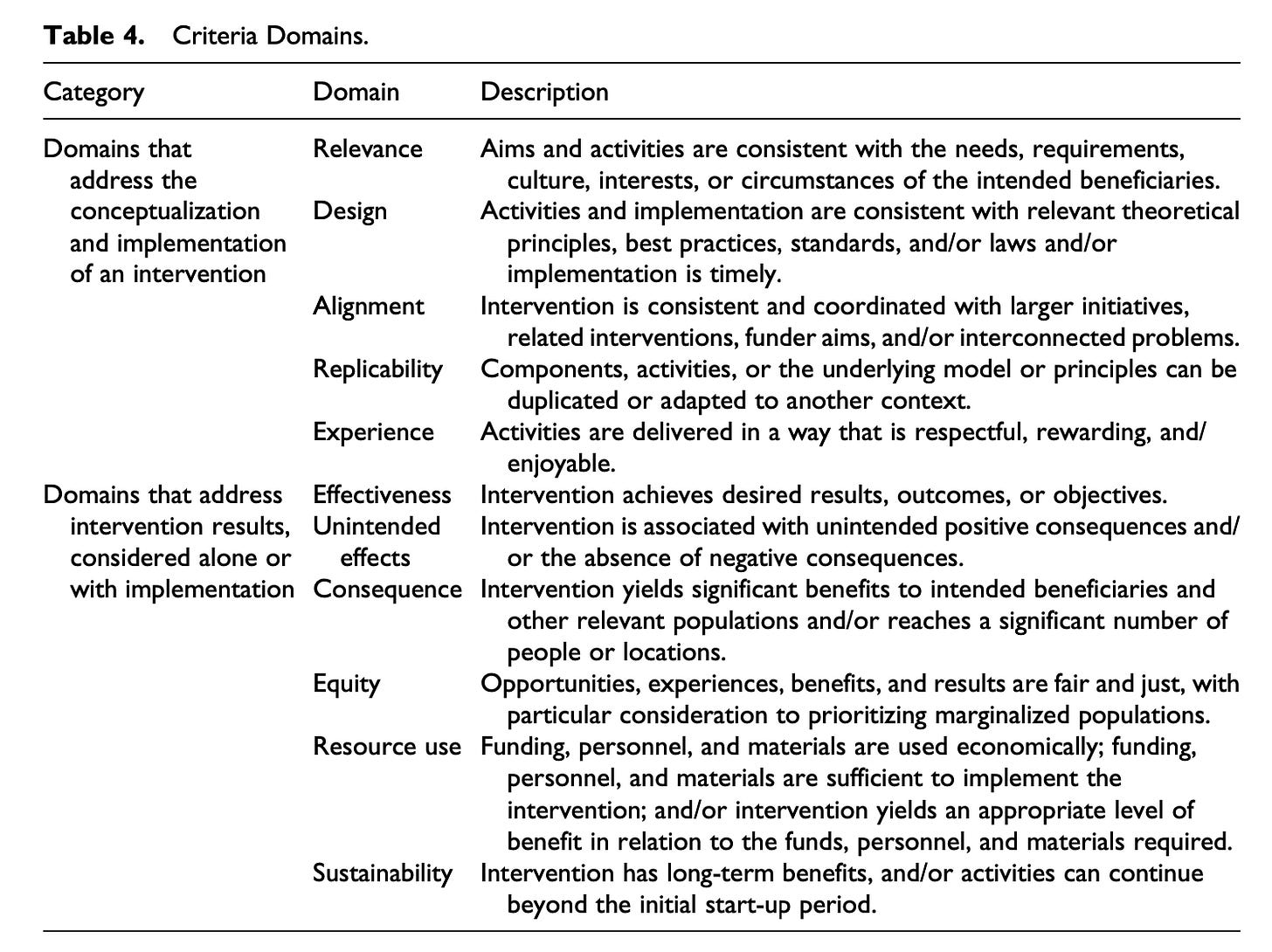

Now that we've laid out some basic ideas about criteria, let's turn to Rebecca Teasdale's popular article (1370 views and downloads as of August 2024). In her review of the literature and a sample of evaluation reports, Teasdale found that that there are many different kinds of criteria and summarized these into 11 domains. Some of the domains are about the setup and implementation of the evaluand while others are about the results. For example, criteria in the "effectiveness" domain concern the extent to which an intervention achieves its desired objective. Less obvious domains of criteria include "alignment", the extent to which the intervention is coordinated with other initiatives. For example, an anti-drug program in schools might meet criteria for effectiveness while failing to meet criteria for alignment if it ends up contradicting the school district's approach to drugs.

In Teasdale's table (pictured above), we see all eleven domains of criteria. It's hard to imagine a better starting point for answering the question "what should I evaluate about this program?" than this. Few projects have the budget to include criteria from all of these domains, but presenting these as options for a client seems like a great way to start a conversation about the scope of the evaluation.

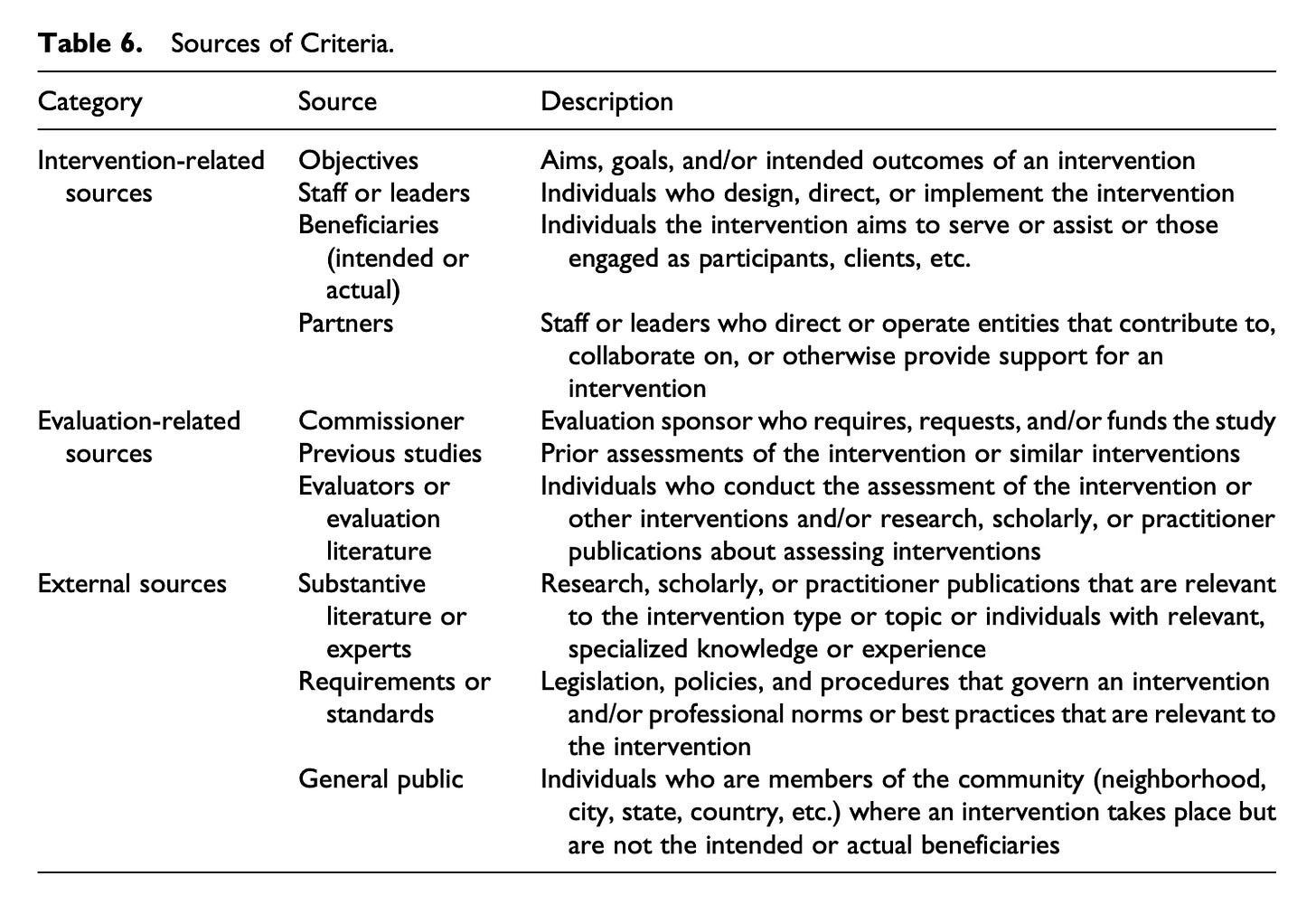

Next, Teasdale presents a similar roundup of the sources of criteria - that is, the kinds of people, organizations, and documents that nominate particular criteria. Some criteria are suggested by the objectives of the program, while others are suggested by experts or the general public. I particularly like the fact that Teasdale allows non-humans (documents, organizations) to nominate criteria.

Teasdale argues that transparency about the sources of criteria can help evaluations to be more democratic. Metacriteria are obviously at work here: we might want all criteria to be selected by experts or we might want all criteria to be selected by beneficiaries. We might want a nice balance of many sources or a balance minus parties who are directly benefited by positive evaluation results (e.g. staff). Setting the metacriteria for sources could be an important part of the project charter.

This post is of the "catching up and keeping up" variety. I agree with Teasdale, Alkin, and Ozeki that the literature on evaluation criteria is too limited. Many evaluators I know did not receive any explicit training on the importance of setting criteria, the possible domains of criteria, or why the sources of criteria might matter. These topics are obviously fundamental, and we haven't even gotten to the issue of how to actually choose among possible criteria, set thresholds for them, or handle uncertainty about them - topics about which I look forward to sharing more with readers in the future.

I’m enjoying your articles. Mathea Roorda’s PhD thesis may be of interest on characteristics of defensible criteria for program evaluations: https://minerva-access.unimelb.edu.au/items/e170c280-f7cc-59ca-a879-5003a1659a6b