What is Efficiency?

Evaluators have a lot to contribute to the public conversation right now.

In the coming months and years it seems likely that Americans will be hearing a lot more about governmental efficiency. Efficiency is obviously a core concept in evaluation theory, and it is a concept which I would argue belongs more to evaluation than to any other discipline. Efficiency is also one of those concepts that most people feel they grasp intuitively but have a difficult time defining in words. Most of the definitions people (including very savvy businesspeople) will give, suffer from the same few problems:

Overly narrow: often focused on monetary efficiency, to the detriment of nonmonetary but very real outcomes

Purely stipulative: actually assert an arbitrary meaning for the purposes of argument rather than describing the concept

Purely ostensive: are actually an example disguised as a definition

A proper definition of efficiency would tell the whole truth about it so that we include things like time and opportunity costs. It would avoid starting off by saying “Suppose we define efficiency as X, then it follows that Y…”, since such stipulative definitions would need to justify their premises, deferring the task of defining efficiency. It would also not simply describe examples of efficiency and inefficiency and leave us to reason by analogy to our own cases. I’ll give my own definition of efficiency in a moment. First, however, I want to explain some of the things that evaluators know about efficiency. If these facts somehow make their way into the public conversation about efficiency, I venture that we will be far better off than where we are now. I conclude with some suggested talking points for evaluators to help you approach this issue in your communities.

Lesson #1: Efficiency is More than Minimizing Costs

Perhaps the single most common way that “efficiency” is used in the world of business and politics is as shorthand for cutting costs. For example, if you had a plan to say, fire half of the staff of a Federal agency based on whether their Social Security Number ends in an odd number, this would certainly cut costs. However, to go on to claim that this would not result in any ill effects downstream, is a mere hypothesis. One needs to claim that there would be no other ill effects in order to remain within the discourse of efficiency because efficiency is a relationship between inputs and outputs.

To begin to estimate the effects of such a dramatic cut in costs, we would need a thorough evaluation of the agency. While it is likely the case that some positions could be eliminated without much loss of function – this is trivially true of any bureaucracy – we would certainly need to know which ones are critical and which are not. This is not a situation in which randomization is useful.

Lesson #2: Efficiency is More than ROI

A very common stand-in among businesspeople for assessing efficiency is return on investment (ROI). ROI is rarely used by evaluators because it doesn’t account for the time horizon at which investments pay out, so it isn’t even very good for business decisions.

However, benefit-cost ratios (BCRs) are a related concept in cost-inclusive evaluation that does include discounting, that is, the time value of money. A BCR greater than 1 tells us that a project is financially producing more value than it consumes, while a BCR less than one tells us that a project is a net loss financially. We are getting warmer in our search for efficiency, since this is a relationship between inputs and outputs, but we should consider what the BCR isn’t telling us to understand why it isn’t the same thing as efficiency. A project with a BCR = 1.3 creates $1.30 of value for every dollar spent on it, so we can say that this is a good deal financially. What we don’t know from the BCR is how long those benefits take to materialize, what the actual total benefits or costs are, or what nonmonetary costs and benefits were involved. Not even the most hardcore fan of economics will claim that it is possible to monetize all costs and benefits – the people who try to do this for a living are usually the most convinced that you shouldn’t do it for everything. Of course, there are some workarounds such as willingness-to-pay studies, but these are used for estimation purposes only – they don’t yield real prices because they concern goods for which we don’t have real markets or for which markets are very distorted.

If we make the mistake of thinking that efficiency is basically a BCR, we might just go around increasing BCRs of agencies as the nonmonetary costs pile up. Does it cost money to do health inspections of meatpacking plants? Since health permit fees are paid whether facilities are inspected or not, firing inspectors and cutting down visits would decrease costs without decreasing revenue, which would undoubtedly increase the BCR of the agency. Lurking outside the BCR is the nonmonetary cost of people getting sick from wave after wave of bacteria-infested flesh (and this is before the budget cuts). The only way to capture these hidden, nonmonetary costs would be a nationwide cost-benefit analysis of the work of the agency.

In my own work, the most common uncounted cost I see is time. Often, this cost is very high because agencies are acting under mandates for which they are understaffed. This causes delays in contracting and service provision at every level. I once met a neighbor who moved to California to work at the Veterans Administration, only to be informed that there would not be anything for her to do for several months. She waited at home, collecting a paycheck, until she was told to report for work. Most VA facilities are understaffed. None of this information would be captured by a BCR, since BCRs don’t directly include time.1

What all of this tells us is that efficiency is a relationship between inputs and outputs in which there are almost always multiple inputs that can’t be easily captured as a ratio between two simple quantities.

Lesson #3: Efficiency Usually Involves Multiple Outputs

Once we get beyond cost-cutting and ROI, we leave the realm of what normal people think of when they think of efficiency. Once you have the idea of efficiency as a relation between inputs and outputs with multiple inputs you are at least thinking like an evaluator. At this stage of the conversation, those trained in social science reach for their favorite power tool: multiple regression. Using multiple regression we can easily take many inputs as predictors of a single output (e.g., monetary benefit) and then compute the predicted output level of any case.

For example, if we suppose that various agencies are all trying to produce monetary outcomes and all have a certain quantity of resources (budget, staff, office locations), then we can use a model to calculate the expected output of any agency. If an agency exceeds that expected output, they are more efficient than average, and if they fall lower than the expected output, they are less efficient than average. A second benefit of this approach is that we can use other predictors of outcomes to adjust for different factors, such as whether the agency is located in high-poverty areas or whether it is critical for defense. If this sounds advanced, know that evaluators have been handling efficiency this way for a generation.

So what’s the limitation? Well, the issue is that the standard form for a multiple regression is this:

That’s one Y-value representing the output, a lot of X-values representing the inputs, and an error term for the model residuals (along with our betas, which are the weights for our inputs). To use this method, we need to boil down our outcome into a single variable. Can we do it? The truth is that usually we don’t want to. Try to think of any actual thing you’d like to happen efficiently and you’ll see what I mean.

Commute: you want it to be fast and safe

Bank transfer: you want it to be fast and go into the right account every time

Virus scan on your computer: you want it to be fast and complete and sensitive

Surgery: you want the patient to be under sedation for as short a time as possible and the surgeon to perfectly execute the procedure and minimize post-operative complications

Oh yes, and all of these cost money, but isn’t it funny how secondary money actually is to efficiency in these randomly-chosen real-world examples? The main factor that keeps coming up is time. We could valiantly attempt to monetize all of these nonmonetary outcomes like time, safety, accuracy, and health (and sometimes that’s exactly what we will do) but doing this can make it very difficult to compare between alternatives in which there is a different mix of outputs.

For example, who is more efficient, a surgeon with a 99% success rate for a procedure and a mean surgery duration of 35 minutes or a surgeon with a 90% success rate for the same procedure with a mean surgery duration of 27 minutes? We could monetize hospital time and patient health, but collapsing these into a third outcome variable of money conceals some valuable information about the tradeoffs we are making between the two surgeons.

What if we didn’t have to choose a single output?

This is the motivation behind Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA), an optimization technique used to measure efficiency. DEA gives us a technical working definition of efficiency:

For any decision-making unit, efficiency is the ratio of its total weighted output to its total weighted input, where weights are non-negative and any unit is allowed to use the weighting system adopted by any other unit (universality). This can be mathematically formalized as a ratio of the distance from perfect efficiency to the efficiency frontier over the distance from perfect efficiency to the observed output levels of the systems.

There is too much to unpack here for a single post, but I promised a definition, and there it is. I’ll describe each part of it. We want to look at all the inputs and all the outputs of the system. Different decision-making units will use different mixes of each inputs and get different mixes of outputs. To compare them, we need weights like the multiple regression above. We are now in the territory of linear programming and optimization, choosing values that will maximize the values of our equations. Modern computers handle this easily. We just need to choose the weights that optimize efficiency. In fact, we can allow the agencies being studied to choose their own weights provided they allow other agencies to be judged by the same standards (this is the universality part). In theory, the agencies should all choose the criteria that maximize their efficiency as a ratio of outputs over inputs, so we can anticipate what a rational actor would choose and use that function.

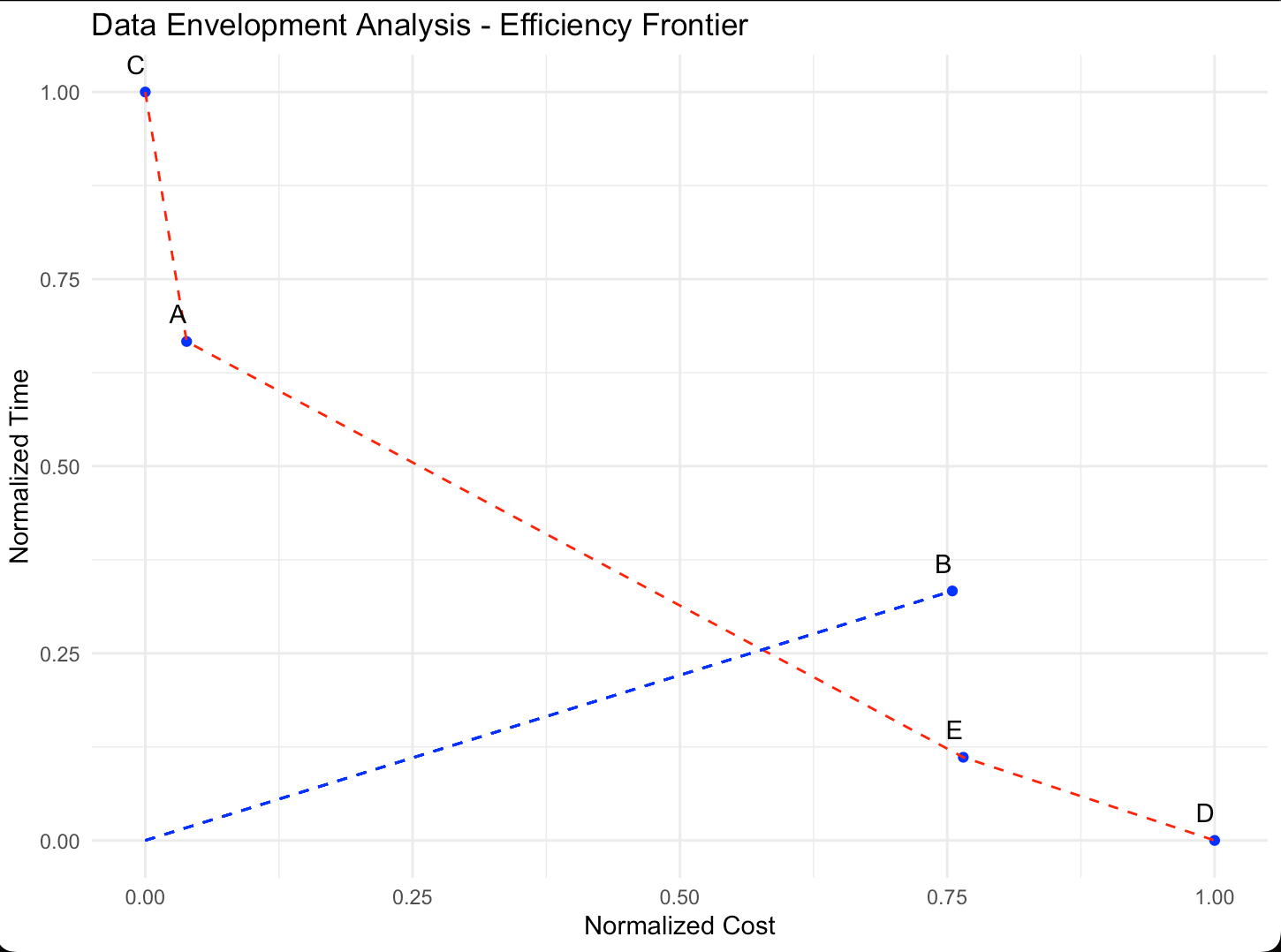

The efficiency frontier is comprised of the decision-making units (agencies, firms, organizations, people) who are the best at using at least one input to maximize weighted output. For example, the efficiency frontier for surgery will include the fastest surgeon, the cheapest surgeon, and the most precise surgeon, even if these are three different people. Suppose that they will all be judged in terms of procedure success rates and minimizing post-op complications. What Data Envelopment Analysis allows us to do is to draw a line between these surgeons in multidimensional statistical space, called the efficiency frontier. Once we know where the efficiency frontier is located, we can calculate the distance between any surgeon and the efficiency frontier. We can also calculate the distance between any surgeon and an imaginary surgeon who can achieve the same output with 0 inputs.

The mathematics behind this idea of efficiency extends to as many dimensions of multivariate space as we require, so we can have lots of inputs and outputs. Not only does this method show us which units are inefficient (anything to the right of the efficiency frontier) but it also gives us a mathematical suggestion for the optimal inputs that would help bring that unit back towards efficient functioning.2 If this method sounds like an incredibly advanced decision-making technique, understand that evaluators have been using it for four decades.3

What Evaluators Need to Communicate about Efficiency

Now is the time for evaluators to start talking publicly about what efficiency is and is not. If we don’t, the “common sense” definitions of efficiency will be used instead of the definition that our field has labored so hard to bring into existence over a lifetime of theoretical inquiry and practical experience. Here are your talking points:

Efficiency is not the same thing as cost cutting. Cost cutting results in inefficiency if you cut the wrong things.

Efficiency is not just about money. Even if it is possible monetize certain costs and benefits, this usually obscures tradeoffs. Remember that we want government to work quickly, ethically, and transparently as well as cheaply.

Efficiency analyses need to take into account all the inputs and outputs, even things that are hard to measure (e.g., people who get sick from contaminated food), before they can claim to understand how to increase efficiency.

We usually want to be efficient about the use of multiple inputs and outputs. There are also usually multiple ways to be efficient with resources (i.e., to be on the efficiency frontier).

We need to conduct systematic evaluations (preferably by a neutral third party) to determine the efficiency of systems. We need even more detailed evaluations to understand how to improve the efficiency of systems. Evaluations are a good investment.

The one caveat to this statement is that BCRs do include discounting. However, since my example took place within one year, most economists would not apply discounting. In the above statement, I mean that the problems with delays are simply not part of the monetary ratio.

This assumes that the input mixture can be tuned in a linear fashion, which is often difficult for practical reasons (e.g., step costs), so watch out not to give nonsense recommendations. This is another advanced reason why cost-cutting measures often fail to generate promised efficiencies.

Sexton, T. R. (1986). The methodology of data envelopment analysis. New directions for program evaluation, 32, 7-29.