Simulations for Evaluation Standards

Prediction, prescription, and standing in line at Disneyland

What if we could use simulations to help us set defensible standards for evaluations? In this post I’m going to argue that doing this would improve many evaluations, for two reasons: 1) they require us to explicitly model how the evaluand is supposed to function, and 2) they allow us to test rules and assumptions algorithmically—something humans are famously bad at doing consistently.

Standards

The Chinese philosopher Mozi (c. 470 BC – c. 391 BC) said that "To accomplish anything whatsoever one must have standards.” While we can debate the “anything whatsoever” part of this dictum, I don’t think we can debate it in evaluation. Standards are the specific propositions that must be true of the evaluand in order for it to count as meeting our criteria. Criteria, in turn, are the general dimensions of merit and worth of the evaluand. “Speed” is an example of a criterion, while “runs at least an 10-minute mile” is a standard.

We need standards in evaluation because performance data do not speak for themselves. The runner ran a 10-minute mile. So what? Is this good enough? The standards capture the dimensions of the situation that are relevant for us to make that decision. When I was learning to run again after being in a wheelchair for a few months, a 10-minute mile was a good standard. While I was in the wheelchair it was not a good standard. Today, I am on the other side of that standard. The purpose of the evaluation also matters: why does my speed matter? It shouldn’t matter for an office job, but it might for a firefighter.

As you are perhaps beginning to appreciate, setting standards is actually much more complicated that measuring performance. It’s a pity that most evaluations probably spend at least 100 times the resources on the latter. It’s also a pity that most evaluators have had no formal preparation in this area.

As we work through these standards, it’s important to hold on to the idea that benchmarks (criteria and standards) are normative claims, that is, they state what we want to see if the program is working. Predictions are a kind of descriptive claim, namely, what we expect to see, given how the program is likely to operate. The exercise I’m proposing connects these by showing us, in advance, whether our standards are realistically attainable and giving us an opportunity to ground our standards or revise them.

Sources of Standards

Previously, I’ve written about Rebecca Teasdale’s 2021 roundup of the source of evaluation standards, which which she includes the following 10 sources:

Objectives

Staff or leaders

Beneficiaries

Partners

Commissioner

Previous studies

Evaluators or evaluation literature

Substantive literature or experts

Requirements or standards

General public

These sources are mostly people or documents written by people. The mundane ontology is that “standards come from humans”, which is true in a proximal sense. However, there is another major possibility, which is that standards can come from non-humans, such as the mind-independent world or intelligent machines. I’ve argued elsewhere that I think we tend to ignore the agency of the non-human world to our detriment, particularly if we are trained in the social sciences.

One practical reason for turning to non-humans to help us with standards can be that the humans have no idea what the standards should be. Another reason is that the humans are only providing us with arbitrary standards. Sometimes funders really want to see a “75% success rate” for the program but can’t explain where this proportion came from. When I see a round number like this, I know there’s a very good chance it was pulled out of a hat.

A simple simulation

Suppose you are evaluating a training program designed to help company hiring managers learn how to write a proper job description. It focuses on important topics like learning to set proper salary ranges for positions requiring given levels of experience and education using market data, clearly distinguishing between multiple levels of seniority within the same career track using criteria besides “years experience”, and the difference between general skills available in the market and specific skills to be taught on the job. The outcome variable will be the quality of job postings produced by the hiring managers before and after the training, as scored by competent instructors with good rubrics.

A simple simulation might go something like this:

a sample of typical pre-training job descriptions and a sample of typical post-training job descriptions is collected (if these are not available, it is alright to create some for the purposes of the simulation)

the two samples are scored using the rubrics

The mean difference in each dimension is calculated for the two samples, as well as the sum scores, if a numeric weight and sum (NWS) approach is valid

Standards are set at the mean difference between the two samples, e.g., the training is expected to increase scores on the rubric by 22% on average, ± 2 points

Already, this simple simulation has done more to ground our standards than most professional evaluations. I covered some other simple simulations here.

A Markov simulation

Now suppose we have a more detailed learning theory about how hiring managers learn to write a proper job description. Suppose that we believe that they are under organizational pressures to produce job descriptions that are silly, even when they know better, and this actually deskills the hiring managers. Under some circumstances, they require retraining in order to avoid publicly embarrassing their organization via job postings. We might also posit that there are different levels of mastery of the core skill, corresponding to Bloom’s taxonomy, and that the hiring managers are climbing the ladder of these skills and sometimes climbing down.

If this learning theory is true, then we are saying that there are multiple states of the process of learning and that transitions between states is possible. With a few more assumptions (recurring behaviors, Markov cycles, long-term dynamics, memorylessness), we can build a Markov model of the learning process of participants. Julian King’s excellent post on using Markov Models in evaluation will get you thinking in Markov models quickly.

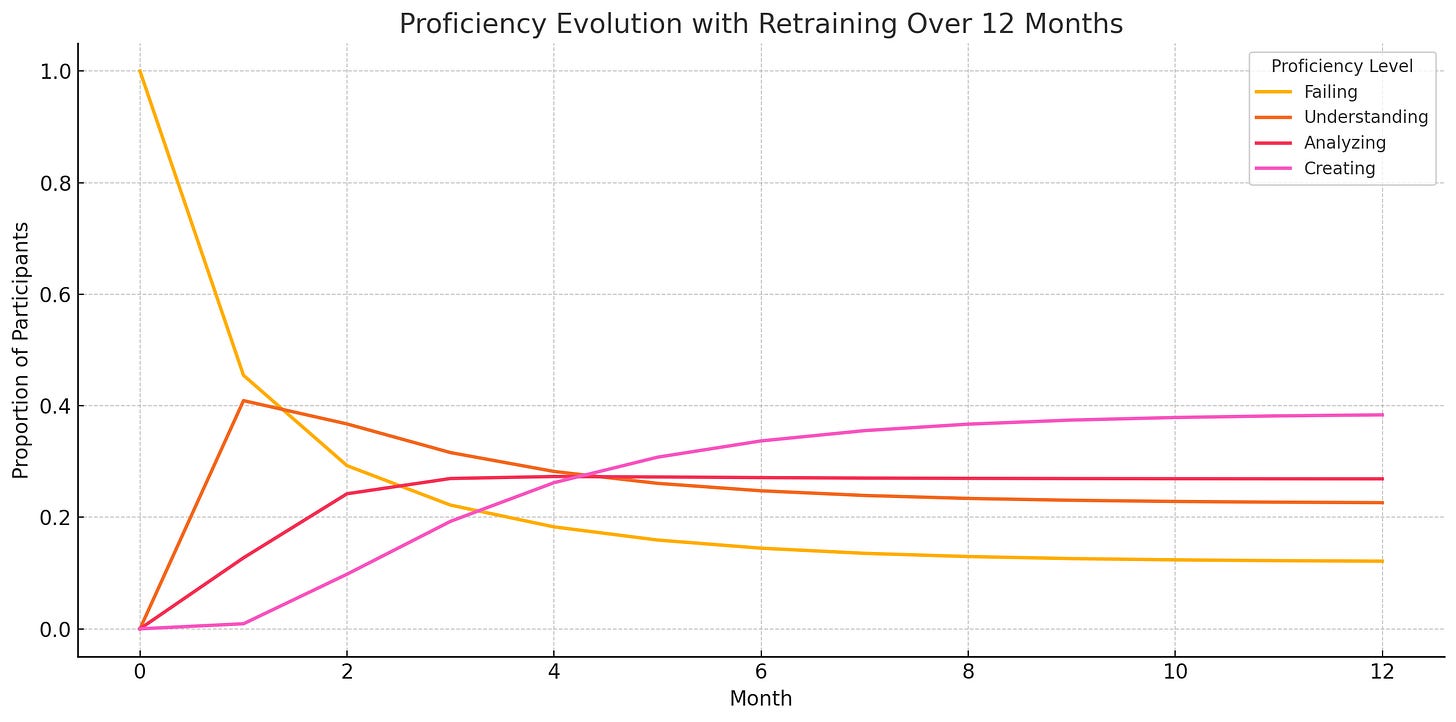

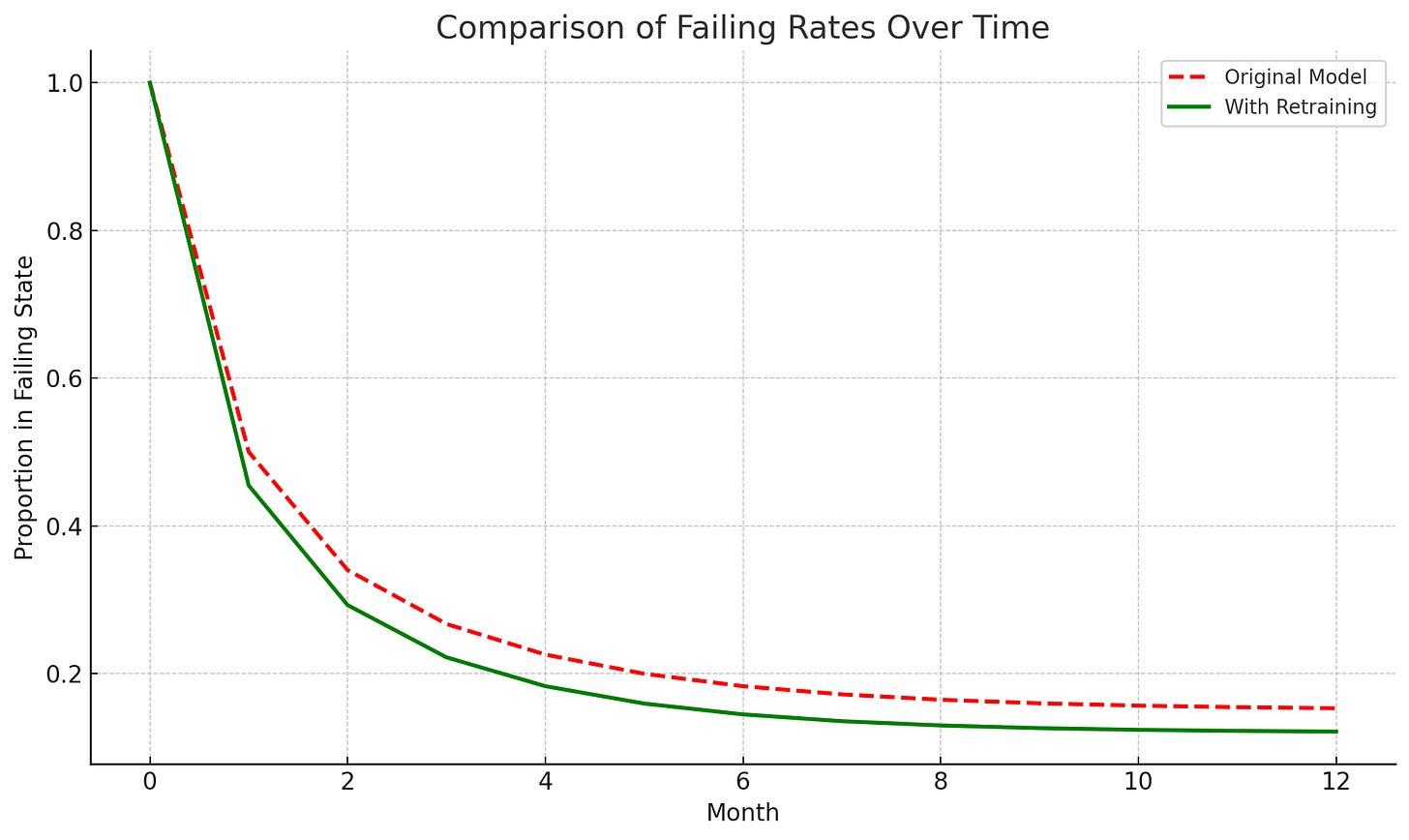

For our example, if we believe that, for every hiring manager we train to write better job descriptions, 20% will achieve at least a level of proficiency of Understanding, 20% will achieve at least a level of Analyze, 20% will achieve the ability to actually Create a posting from scratch, and 40% will continue to Fail at writing job postings, then this is what we expect to see if we measure proficiency right at the end of the first cycle of the program. However, what should we expect to see if we measure proficiency a year later? Also, let’s imagine that we trial another version that makes it possible for managers to retake the course, which boosts their competence to a higher level. In order to find out the results we should reasonably expect to see, we can use a Markov model with a standard time period, of say, 1 month, and then specify the probabilities of state changes that occur each month. For example, a hiring manager with the lowest level of understanding at the end of the course has a high probability each month of returning back to failing performing, while a hiring manager who attained the highest level of Competence is much less likely to recidivate back to failing level. Likewise, each month, each participant has a certain probability of returning to retake the course, which in turn gives them a probability (conditional on the former) of improving their proficiency.

Once we know the rules of what happens at each turn of the simulation, we can program R or Python to let us know how it’s all likely to turn out for everyone in 12 months. We can play around with multiple versions of reality in this simulation and choose the one that makes the most sense.

Agent-based simulations

Maybe there are different types of hiring managers and they behave differently. Some hiring managers, through no fault of their own, are themselves victims of shoddy hiring practices and have no idea what they are doing. Some hiring managers are just cutouts for the whims of the C-suite, who actually write the silly job descriptions. Other hiring managers have both the background and the ability to implement the training. If we had a rough idea of the breakdown of this typology, we could make much better predictions about performance and thus set better standards. If we know this information, perhaps through an anonymous questionnaire, we could make better predictions and not be so surprised when a large proportion of our participants continued to churn out silly job postings no matter what we do.

Does anyone use models this complicated? Actually, yes, they do.

The documentary channel Defunctland features an in-depth episode on the development of Disney’s controversial Fastpass system, which allowed guests to make advanced reservations for rides instead of standing in line. To address the question at the heart of the documentary, “Did Fastpass increase or decrease wait times?”, the creators use an agent-based model of park attendance. This model featured different kinds of agents (like tourists versus regulars) and different attractions with various demand levels. The documentarians modeled scenarios with no Fastpass, the original Fastpass, and the new Fastpass. While their conclusions were interesting, the main point is that the system dynamics they elucidated were theoretically available before collecting any performance data.

In fact, the simulation probably provided more accurate predictions than the early experiments with the Fastpass, since the experiments tested the effect of Fastpass among only a few patrons, not on all the patrons, as would eventually become the status quo at Disney. (The system-wide effects of everyone potentially being able to skip a line or two turn out to be very different than letting a handful of people do this.)

The simulations show, among other things, that we should only expect modest differences in overall wait times for rides, despite a billion-dollar investment. Moreover, for the guests who do not use the Fastpass system, the simulations showed that wait times should be expected to increase. This information is exceedingly helpful for setting standards by which to define whether the system was a success. For example, we might say that the system will be a success only if it meets multiple conditions: 1) average wait times decrease by 30 minutes per user, 2) wait times between users and non-users of the Fastpass account are no more than 20% different, 3) average number of rides per person increases. (This latter turned out to be the main positive outcome of the Fastpass.) The simulation results will give us an indication of whether these standards are defensible or whether we are wishing upon a star.In fact, the simulation probably provided more accurate predictions than the early experiments with the Fastpass, since the experiments tested the effect of Fastpass among only a few patrons, not on all the patrons, as would eventually become the status quo at Disney. (The system-wide effects of everyone potentially being able to skip a line or two turn out to be very different than letting a handful of people do this.)

The simulations show, among other things, that we should only expect modest differences in overall wait times for rides, despite a billion-dollar investment. Moreover, for the guests who do not use the Fastpass system, the simulations showed that wait times should be expected to increase. This information is exceedingly helpful for setting standards by which to define whether the system was a success. For example, we might say that the system will be a success only if it meets multiple conditions: 1) average wait times decrease by 30 minutes per user, 2) wait times between users and non-users of the Fastpass account are no more than 20% different, 3) average number of rides per person increases. (This latter turned out to be the main positive outcome of the Fastpass.) The simulation results will give us an indication of whether these standards are defensible or whether we are wishing upon a star.

Prospective evaluation

If you were to use a simulation to conduct an entire evaluation, rather than using it to help set the standards for one, this would be a prospective evaluation. While uncommon, prospective evaluations have actually recommended by the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) since as early as 1990. GAO lamented that “most proposed programs are put into operation—often nationwide—with little evaluative evidence attesting to their potential for success.” The fact that we don’t see lots of prospective evaluation in government today is just one clue among a great many that the rest of the government doesn’t listen to the GAO.1

An example of a prospective evaluation using a simulation is detailed in Alter and Patterson’s (2007) paper on No Child Left Behind. Using a simulation based on the available performance data, the prospective evaluation found that between 80-100% of Minnesota elementary schools would fail to make adequate yearly progress under NCLB, even using the most bullish growth estimates. This would result in most schools in the state facing legal sanctions. The total cost of implementing all of this at the state level would exceed the increase in funding promised by the federal Department of Education. The Minnesota legislature decided to do what it could to seek waivers out of the NCLB requirements.2

The difference between prospective evaluation and what I’m advocating in this essay is that prospective evaluation treats the simulation data as performance data, whereas I’m talking about using simulations as a guidepost to set standards. This latter approach is more difficult because we need to consider the difference between what our simulation tells us and what our standards should be.

Why you should consider running a simulation to set standards

The process I’m proposing is this:

Learn enough about the program and the participants to make a simulation

Run the simulation, perhaps with a few different contingencies

Use the simulation results to make a prediction about the most likely outcome of the program

Use this prediction to inform standards for the program, registering a probabilistic judgment about how likely the program is to reach that standard

I’d like to end with a couple of observations. Even if we only carry out step one of this process, we will be doing more than most professional evaluations achieve. This is a great time for qualitative research. We need a broad frame of inquiry to answer the kinds of questions that the Defunctland simulation was trying to tackle: how many types of people are involved in this system, what are they like, what are the states they pass into, what are the most attractive places to be in the system? The process of chasing down these types of questions will give you the kind of information that makes writing about the program easy, making it so you have too much to say rather than not enough.

Steps 2-3 of this process, while they may seem difficult, are really for the computer. If you make it to step 2, you are just a few hours away from having a working simulation of a program. This is a very valuable product all on its own - something that industrial engineers charge lots of money to create. If your simulation is wrong in a way that surprises you and the stakeholders, I guarantee you that it will be wrong in an interesting way and that you and the stakeholders will feel the whole exercise has been worth it. Imagine putting all your best thinking into a simulation of program processes, registering a prediction, and then finding out that something completely different is going on – where would you have been without the model?

The last step of the process gets conceptually tricky once again. We need to be careful not to conflate our prediction about the results of the program with our benchmarks for program performance. These ideas are related to each other but they are not the same thing. Using a simulation, we may find that it is unlikely that Fastpass will decrease average wait times at Disneyland or that our training will actually help hiring managers stop writing silly job descriptions. However, in both cases, our benchmarks will still be high: we want to get wait times down and we want job descriptions that don’t result in the organization getting ratioed when they post them to social media. Our benchmarks are normative standards that need to be defensible. Our simulations produce predictions about performance. The relation between them is that we can treat our simulation as a dry run of the performance of the program so that we can preview the inevitable (hopefully, if the evaluation is symmetric) confrontation between benchmarks and performance. If this preview reveals that the standards for the program are nigh unattainable, this prompts us to ask crucial questions about the evaluation: are the standards defensible in this context and, if they are, what is our prior that the evaluand will meet them?

If your standards can’t survive a simulation, they probably can’t survive reality. Better to find that out now—before the end of the line.

Since 2019, Federal agencies have been required to make a simple report to Congress consisting of 1) what the GAO asked them to do, 2) the status of those recommendations, 3) and explanation of any discrepancies between the GAO’s recommendations and the agency’s own plans. Most US Federal agencies have failed to comply fully with this law (“GAO-IG”) and several have completely ignored it: Dept of Energy, Dept of Defense, Dept of Labor, Small Business Administration, and Dept of Interior. The fact that this law had to be made in the first place, and then was subsequently flouted, speaks volumes about federal agency accountability to Congress.

History provides us with an amusing postscript. In 2004, the findings of the prospective evaluation were criticized by the commissioner of Minnesota’s state department of education on the grounds that the methodology was “based on the assumption that the law won’t be changed for 11 years… To assume that there will be no changes to this law over the course of 11 years is to ignore reality.” NCLB would be repealed by Congress 11 years later.